Looking Back on 2025

Some words and photos to look back on the year that was from So What! Editor Steffan Chirazi.

Jan 11, 2022

Steffan Chirazi

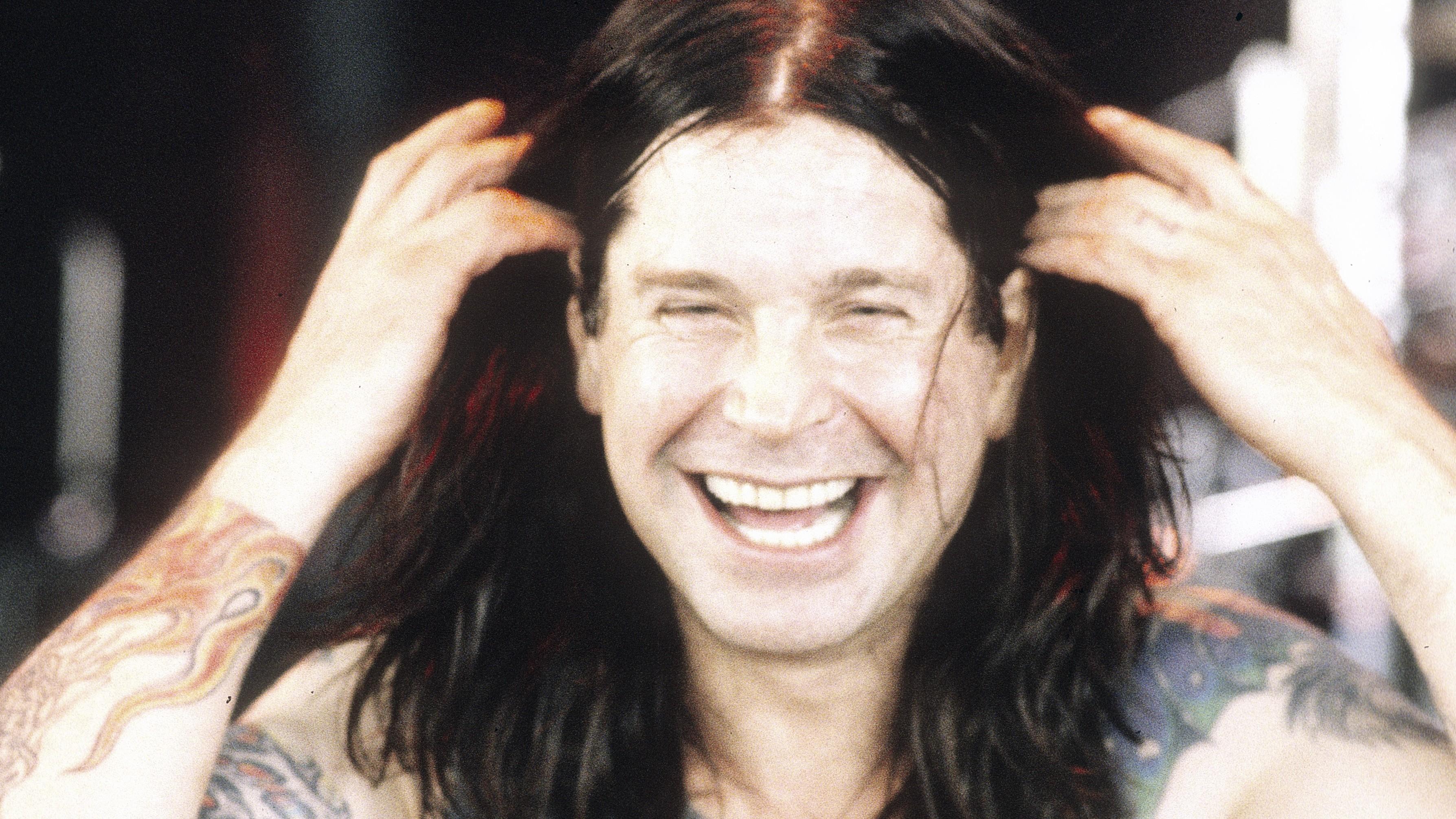

It is fair to say that the music business has always carried with it a fair amount of wide-boys, bullshitters, egotists, and over-staters… people who talk a good game but cannot deliver. It is also fair to say that there are also a few, a precious few, who fly quietly and serenely under the radar. They don’t seek public adulation for their talents, however, were they to start telling you what they’ve actually achieved, it would be an evening’s worth of references, one which would require dinner (you’d be buying as a thank you). Just in case you’re in any doubt which one reflects Bob Jens Rock, it is the latter.

The Canadian-born Rock is undoubtedly one of the nicest, most genuine people I have met in my decades around the music world. He is also a supremely talented producer, engineer if he wants to be, and musician. You know those gold and platinum wall plaques people get sometimes? I’d wager that the ones he’s received could cover the Arc De Triomphe because if Rock was metal, he’d be guaranteed platinum. Ask Metallica, Mötley Crüe, David Lee Roth, Bon Jovi, Bryan Adams, Michael Bublé, Aerosmith… yeah, the list goes on.

Rock is also a fine guitarist, as evidenced in his early band, the Payolas, and later with Rockhead, who supported Bon Jovi. And besides playing on the Crüe’s Dr. Feelgood, he was the bassist for Metallica’s St. Anger. Rock has also won several Canadian Juno awards, and in 2007 was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame by the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences. In 2014, he won a Grammy for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album with Michael Bublé’s album To Be Loved …but enough! He won’t like this digital victory parade. Besides, we’re here to discuss his recollections of The Black Album era for So What! Despite having somewhat done the circuit with such discussions recently, Rock was happy to sit and chinwag one more time about the album, which has turned out to define his career.

Steffan Chirazi: First of all, I want to start by framing for people what the overview role of a producer was in the ’80s and ’90s. I think it’s probably quite different now from how it was then. You’ll tell me, but I’d written down, “friend, Roman, countryman, sound getter, performance coaxer, and therapist.” Does that resonate as what a producer was in that era, that time?

Bob Rock: Well, I can only speak for my experience at that time. At that point, I was making the first steps of switching roles from being an engineer, mixer, and kind of like musician to being a producer. So before that, I had done Kingdom Come, The Cult, Mötley, Electric Boys, etc., so when I got to Metallica, I was fully immersed in being a producer. And I guess the way I see a producer is still true to what I do now, and that is I just help whatever artist I’m working with make the record that they want to make. Whether that’s sonics, lyrical, musical, tempos, therapist, friend, a sounding board… you earn their trust. I would say that a great example of how I see a producer would probably be Jimmy Miller with the [Rolling] Stones. He made them a better band but didn’t change them, and that’s what I always strive to do. I never ever started out changing Metallica, I just wanted to bring out what I thought was the best of them, and I think that’s what a producer does.

SC: We are going to largely talk about The Black Album, so let’s kick that off with a fairly perfunctory question. The initial contact: how long was it from the moment that management called you to speak with the band about doing the record to actually speaking to the band about doing the record?

BR: Maybe a month? The conversation was with my manager, Bruce Allen. I visited him in the office, we were talking, and he said that Peter [Mensch] and Cliff [Burnstein] had talked to him about whether I would be interested in mixing Metallica’s next record. And at that point, having (as I told you) changed my role so-to-speak, I wasn’t really into just mixing a record, so I just said I’d pass. We didn’t hear anything, and then I guess they decided to come up and see me in Vancouver. So they flew up to Vancouver, and we spent maybe a day and a half, or two days, together just talking about it. I think that’s when maybe they realized that we could work together.

SC: When you were contacted, were you aware of how much the drum intro to “Dr. Feelgood” had contributed to the overall approach?

BR: Not, not really. But I will say, just prior to that, I bought the Justice album because all the skaters in the neighborhood had Metallica t-shirts. And I remember they played a place when I was doing the Black ’n Blue album. One of the guys in Black ’n Blue, I forget his name, went to see them at this small theater. So the name “Metallica” came to mind. And what changed me was when The Cult warmed up for them on the Justice tour. I went to see Billy in The Cult, and I stayed and saw them live, and what just struck me right away was how big and powerful they were, and you know, the Justice record just wasn’t that. I mean, it was powerful, I guess, but sonically and just the way I heard them live, the record didn’t sound like that. And that’s where I come from in terms of being a producer and sonics and everything: really capturing a band live. So that’s how it came about.

SC: So that was the ethos behind your approach?

BR: There was no concept. There was no plan. I hate to use the word “natural,” but it all just happened. The album and how it sounded, everything, maybe they had a plan, but you know, I didn’t have a plan.

SC: How were those early days?

BR: I can safely say that when we did pre-production in Oakland, and when we were actually getting to the studio, I was always being tested. I was also testing them, but there’s this whole thing about the way I learned to make records, and we talked about how I make records. One of the biggest things is I have everybody play in the same room. Then they told me how they did it with Flemming, and I just said, “Yeah, I’ve heard that people do that, but it’s just not how I do it.” And I told them why I did it. “This is how I learned it. And if you’re interested in doing that, let’s start going towards that and see how comfortable it gets.” I’d never really been around people as intense and actually committed as they were. I started realizing that I was in the room with something very special.

SC: What were those early sessions like?

BR: There were a lot of songs, the lyrics weren’t completely done, they were kind of roughs, and James just mimicked melody. So there were fragments of what the songs were about, but as we went on and he wrote the lyrics, I started learning and getting the stories behind the songs. They worried about sounding too commercial and stuff, but they were interested in having a record that sounded like the records I made. And you know, people think it’s some sort of “commerciality,” that you add these “tricks” to make it “listenable.” That is not how I work. Everything that I suggested, and we tried, was based on how something felt. There’re no rules in terms of how I approach it; it’s always about how it feels. When I add a harmony to a chorus, it just felt that [in order] to bring out the lyrics and the chorus, the feel of it, it needed a harmony. And when we did it, they liked that.

SC: How easy was it to get them to try things?

BR: My observation was that they only knew one way. Nobody had ever said, “Well, you can do this.” Like the bass with Jason. You know, when I first worked with them, his sound was basically a guitar sound, and he played the riff. I said, “You know, Jason, the bass and drums, it’s called the rhythm section.” The bottom end and the weight of The Black Album has to do with Jason breaking away from that mold. So there’s sort of counter bass things more with the rhythm section than just playing the riff. It’s not smarts or anything; it’s just doing records. By the time I did The Black Album, I’d probably worked on 30 or 40 records. And with each record, I learned something, so I brought this bag of what I’d learned, and I just shared it. And they became more comfortable. I knew some of the records they liked, and they were like the records we ended up making. They love Lynyrd Skynyrd, they like Thin Lizzy, and that’s what we were doing. It’s almost like they didn’t know why they liked it, in a funny way.

SC: Jason made a comment to me when we were talking about The Black Album, which blew me away. He said Metallica were the original White Stripes in so far as Lars and James drive so much.

BR: Bands are these strange animals, right? There are always the alpha males, and there’s always that duo, those two guys. It’s just a privilege that I got to be in the room with these guys and get to know them [not just] as people but as musicians and artists, right? Overall it was fifteen years that I was with them, but even in The Black Album, we were there for pretty much every day for a year, twelve hours a day, and you start to learn that there’s a lot more depth. And to me, loving records and bands and, you know, just being obsessed with making records… all of a sudden, I was presented with basically a modern version of what I imagine working with the Stones or Led Zeppelin was like. I look back, and when The Black Album came out – I think I’ve said this before – the reaction to it was much like Led Zeppelin III to me. It was like, “What the fuck is this?” But through the years, Led Zeppelin III is as good as any of their records.

SC: The studio tension is fabled folklore. I’m trying to remember my own visits at the time. I don’t specifically remember anything like this from what I saw beyond normal studio grind, but it’s fabled that there was a moment within the first six months of this project, including the pre-production, where you said, “I am not gonna put up with this. I’m not gonna stick in this project if it carries on with this tension,” and so on and so forth. Is that folklore?

BR: It’s folklore. It’s not true at all. Not at all. Once we got past the wall of distrust which was torn down, they trusted me and, of course, (engineer) Randy Staub with me. There was tension, but there’s tension on every record. I just finished four tracks with Michael Bublé, and there’s tension. There’s always tension because we are all so into this that it isn’t kid stuff. This means everything to us. The only people that really know what happened are the people that were there, which would be Randy and the guys in the band. In A Year in the Life, there are videos of me with Kirk with his guitar solos. That was a moment [where] somebody captured me on film. I was having a bad fucking day, but the fact is, the solo ended up being what we talked about doing, Kirk played amazing, and we just worked through it. So maybe there was a tough three hours where I was in a bad mood, and he felt I hurt him or something, but that went away. People watch the video, but they’re not getting the full picture. I could write a book about The Black Album, and I don’t think I’d sum it up very well in terms of everything that happened. But this is why I still make records, and it still is pretty much the best record I’ve ever made… just that timing. You can’t even duplicate what happened.

SC: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Switching gears for a moment, let’s talk a little bit about your team as well. We talked a lot about the creative body of Metallica here, let’s talk about your team at that time, Randy Staub and Mike Tacci. Bring people through exactly what Randy and Mike brought to your team and just how you would work.

BR: Well, I realized that I couldn’t both produce and engineer. I know what a producer is, and I know what you gotta do, and you can’t really think about the mechanics of it. So I had to find somebody. I did The Cult’s Sonic Temple album with Mike Fraser, who was my assistant forever, but at some point, he went on to do other things. I needed to find somebody, and I had just worked with Randy on a project. He was the assistant engineer on it, he ended up being in LA, so I asked him if he’d do the Mötley album with me [Dr. Feelgood]. We could be in the same room, he was very gifted, and so we just established that relationship. I couldn’t have done it without him, basically. It would not be the same. Because handling the intensity of all the people, the music, overseeing everything, I needed that guy that I could trust, and he was that guy. We were totally a team. You know, there was no description, no job description. The most amazing thing about Randy was that he got my language, and he could do it. If I did something too far, he’d bring me back, and he’s the best engineer and mixer I’ve ever worked with, you know.

SC: Did you find you were “tasking” certain band members with certain jobs? Did Jason have a certain task? Did Kirk have a certain task in terms of supporting the overall body of songwriting?

BR: Well, as I said about Jason, his sound was very much like a guitar sound. He was playing the riff, so to speak. So going through a process of elimination to find a good sound, we ended up with a Precision bass and an SVT, which is pretty much the standard of rock music. There are variances in that; do you follow me? But we ended up with the bass sound, much to his surprise. And then when he got there, he liked that, and he liked the fact that he wasn’t doubling the riff… well, he doubled the riff, but he became a bass player in a funny way. And the thing with Kirk was, I think everybody knows, that [it used to be] at the end of the album he’d just come in and do all the solos. But when he played rhythm on the floor doing the basics, he [also] did solos when he wasn’t thinking of it. When we went to do solos and were stuck, I got Mike Tacci to make a cassette of all the solos that Kirk played while he wasn’t thinking about it. He listened to that cassette, and that’s how he formed all the solos. It was the same thing with James. It’s like he came in with the Chris Isaak tune. He was saying, “I want to sound like that. How do you do that?” And I said, “Well, I can do that for you, and then you don’t have to double, you can sing all the way through the song, and you will get more emotion, right?”

SC: It was also a really vital time in his writing development. So as well as having someone prepared to fully validate him wanting to express his emotions vocally, he had the same lyrically.

BR: I can easily say that the lyrics on The Black Album are the most personal. Do you follow me? There’s not a lot of metaphor. I’m not gonna get into analyzing what he did, but I was showing him how basically the records that we love, a lot of them are not planned. It’s not “bit by bit.” There are performances, there are flaws, there are emotions. And the keys are “The Unforgiven” and “Nothing Else Matters.” Really, that’s where the personal stuff came out to the front, and that’s where his vocal changed. It drew you in. And that’s why dentists and lawyers and everybody bought the album… because there was a human there. He was saying something that they feel, right?

SC: You also got into the lyrics with him, right?

BR: We talked about lyrics, yes. Nobody really talked to him about lyrics, it was a no-no, and you know their rule [back then] where Lars could never talk about anything James did, vice versa. They had this set of rules, right? So all of a sudden, because I was willing to listen, we talked about lyrics and great lyric writers. And you know, I think the lyrics on The Black Album particularly are up there with any great lyrics in history. You talk about “Sad But True,” that’s easily one of the best lyrics personally when I hear it. When you’re doing it, it’s something else. But it’s just so relatable, so fucking good.

SC: Some of those lyrical conversations you would’ve had with him, what kind of stuff did you find yourself getting into with him? How did you push him to push himself?

BR: Well, it gets down to the trust thing, and it was almost like letting somebody out of the cage. Just showing them the door, because there’s this rigid framework that had worked before, that’s what they knew, and they became very successful doing it. But when you open the door, like I just opened doors for them, I said, “This is what I know, and this is what I know the result will be.” All of a sudden, when he didn’t have to record every phrase and then double it… when he could sing a whole verse, he quickly dove into emotive singing. Right? And that’s what he heard. I didn’t tell him; I just opened the door. And when the door was opened, he adapted so quickly.

SC: Which song, if there is one, do you think was underrated on this record? What’s the song that you think always gets overlooked that you’re like, “I don’t get how people miss that one?”

BR: Well, realistically, Steffan, there were so many songs that got released that everybody knows. But it’s known that I love the feel of “Holier than Thou.” I’d never heard that on the radio. Then [when I did hear] it on the radio, and I just cranked it, and I’m sorry but that’s… I still like up-tempo stuff, right?!!

SC: I know that you’re a student as much as a producer. You love to learn from every project. What did you immediately learn from that recording, and now as we sit here talking some decades later, what do you feel you learned?

BR: Well, really, what I learned from them was the commitment and how that commitment pays off when everybody is on the same page. Because so many times there are situations where somebody’s very committed, and other people are not, and it kinda destroys the whole thing. What I found out from them especially is the commitment to excellence and not compromising whatsoever. So that was something that was gonna continue through my whole career. Looking back, I think my best work is when people have challenged me, and I think that goes back and forth too. I think their best work is when they’re challenged.

SC: Do you still find it somewhat unfathomable that you ended up producing an album that sits on the same line as Back in Black, The Dark Side of the Moon, and Physical Graffiti in terms of enormous cultural resonance?

BR: Like I said, I’m so proud of it. At the time, I wasn’t because I didn’t know. The other thing, at least in my career, is that I never really listen to something that I’ve just done, so it took me years to look back. It takes a long time when you work on something to disconnect from the work.

SC: Well, finally, how long did it take you to decompress from The Black Album, and how long did it take you before you did sit and listen to this album as a listener?

BR: Oh, you know, decades. Decades to disconnect from the craft and to be able to listen to it like when I put on, for example, Exile on Main St. Now I can listen to The Black Album. I listened to the whole record maybe a year ago, just by myself, and I really enjoyed it. I disconnected from the craft of it and just listened, like listening to my favorite albums. And it’s one of my favorite albums now. It’s the same with everybody. It’s because it’s a moment in time, and there’s a certain part of what I do, you know, maybe it happens with you, where you just think, “I could’ve done that better.” And then at some point, somebody points out they really like it, and then you look at it, and you go, “Yeah, it’s pretty good.” That’s the process I have.

SC: Well, I’m glad that you finally listened to the entire Black Album again just recently, and I’m really delighted to hear that you enjoyed it. I think it’s safe to say that the better part of a good 25-plus million people were there a while before you, though.

Some words and photos to look back on the year that was from So What! Editor Steffan Chirazi.

Dominic Padua (aka Dom Chi) does many things very well, including the art of marbling. Steffan Chirazi visits his Sebastopol, CA, studio to learn more.

What you are diving into here is my personal journal with regards to the Back to the Beginning extravaganza. Much of it was written off-the-cuff, and the sheer magnitude of the event means that even now there are still pieces of “thought” swirling in the ether and making brain fall by the hour. These recollections, emotions, and observations are shared reflectively over three separate entries after the event and are split between an initial “post-event download” and then a more chronological reflection on our time in Birmingham…